A bipartisan arrangement is ideal for the reforms:

The chess game, political gimmicks and maneuvering, which have characterized the road towards resuscitation of the national reforms, especially the 11th Constitutional Amendment Bill signals that narrow political interests are at play

Mr Mzimkhulu Sithetho

Managing Director of the Governance Institute for Sustainable Development and Editor-In-Chief of thizkingdom.com

Commitment by the current regime to drive the reforms

The new coalition government led by the Revolution for Prosperity (RFP) has demonstrated a modicum of commitment to the reforms. During the RFP’s campaign trail, the party had placed a high premium on the national reforms. Again, after winning the election, the RFP further reinforced its quest to drive the reforms agenda. However, there is no evidence that the voters’ response the manner it did by giving a novice a mantle to lead the national develop agenda through a vote could be attributed to its pronouncement on reforms. When the coalition government comprising the RFP, the Alliance of Democrats (AD) and the Movement for Economic Change (MEC) forged an alliance, it made a strong case for taking the national reform agenda forward. On the contrary, Professor Motlamelle Kapa, a Professor of Political Science and Administration at the National University of Lesotho takes a swipe at the RFP- led Government for delaying to take steam on the reforms immediately when it occupied state house. Professor Kapa is of the view that the RFP-led Government came late in the day to lead the nation in the national reforms. The Government embarked on a crusade to consult with various sectors on the state of the reforms, the proposed approach and the way forward. About 14 sectors were consulted in this attempt to revive the national reforms after they were thrown into oblivion when the previous parliament got dissolved having failed to pass the 10th Constitutional Amendment Bill, popularly known as the Omnibus Bill. Then, the national reforms had been done another blow when a Mosotho national challenged the declaration of a state of emergency by the then Prime Minister Dr Moeketsi Majoro, a move that had come as a clarion call from the throne.

Then, there was an election in October 2022, which threatened the future of the reforms post elections. Political and development analysts feared that the reforms might not see light of day as their future depended on the attitude of a new regime on the reforms. The government has up to now, engaged in a battle to salvage the reforms with the office of the Prime Minister paying special attention to the reforms process and engaging various sectors on the reforms. This exercise has not been a smooth sailing as it met fierce opposition to an unrelenting opposition bloc, which has since quashed any move taken by the Government side. Though the ruling RFP and its governing allies tried to use their numerical and legislative strength to tilt the levers of authority in their direction regarding the reforms, they fell short of their guns. They tended to douse the fires even more and attracted sterner opposition, which also saw some of their ruling regime’s Members of Parliament side with the opposition. The opposition tended to have regained strength after being whipped to the core by the RFP in last year’s elections. Affirming the views of Professor Kapa is the Senior Lecturer at the National University, Political Science and Administration, Dr Tlohang Letsie, who argues that the RFP could have taken advantage of the low hanging fruits after winning elections.

Dr Letsie opines that the opposition had been taken by shock of the outcome of the 2022 poll. He argues that then, there could have not been much opposition as they were reeling with the pain of losing an election. Dr Letsie argues that, later, the opposition recouped its energy and suddenly it was united and was able to put up a formidable, though not rationale force against the governing regime.

But it made a dent regarding its uncalculated tactics of delaying the reforms so that the voters ‘hated’ the ruling RFP for its lackluster regarding progress on reforms. During the sector consultations, it seemed that a great proportion of those that participated had thrown their weight behind the governing regime on the modality and approach on the reforms. However, the opposition, which had now regained its strength, put up an artificial united front, led by the official leader of opposition, Mokhothu Mathibeli, Leader of the Democratic Congress (DC).

RFP’s political clout tested by the reforms

One of the main characteristics of the national reforms was that it put the RFP’s perceived or real political clout to a test. It was during the consultative meetings and a push for resuscitation of the 10th Constitutional Amendment Bill that the RFP and its governing allies had to pass the litmus test of its actual or perceived political novelty or its political clout. The RFP itself confessed to being new in politics, and knowing little about the national reforms. This seems to have given the opposition the political ammunition to put up an overt and aggressive opposing posture against the RFP-led regime. The opposition was part of the 14 sectors that had been consulted. When the Government was about to conclude its consultation spree, the opposition released its salvo and put up a serious antipathy to whatever the government proposed, particularly with regard to the reforms.

The opposition is the only sector that has been consulted six times, with little progress as they kept on changing positions every time the opposition met the Government side. This overtly frustrated the governing party to the extent that it felt its cause for development was being undermined. Little did the novice regime understand that politics is a game of interests and sometimes, just narrow interests. It is a game of intrigues, gimmicks and chess-playing. The RFP’s weak political clout was exposed during the reform process, the resuscitation of the Omnibus Bill to be specific as the party has not gone deeper into the reform.

Political chess game, intrigues, political maneuvering and gimmicks

The period for the hype to see the 10th Constitutional Amendment Bill presented and passed in parliament marked a critical time in the political minefield of Lesotho. The period was between April - August 2023. There was overt political chess gaming, political intrigues, maneuvering and gimmicks at play. The political chess game was characterized by to-and-fro exchanges, a series of meetings, and presentations of positions as well as give-and-take moments.

On the side of the governing RFP and its allies, there was a bit of patience exercised as the opposition was releasing its salvos time-and-again, against the resuscitation and passage of the Omnibus Bill. The analogy of a chess game is that in a chess game, there are two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess spices, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. The rules of chess as they are known today emerged in Europe at the end of the 15th century, with standardization and universal acceptance by the end of the 19th century. Today, chess is one of the world's most popular games played by millions of people worldwide. In business, chess is an abstract strategy game that involves no hidden information and no elements of chance. It is played on a chessboard with 64 squares arranged in an 8×8 grid. At the start, each player controls sixteen pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights, and eight pawns. White moves first, followed by Black. The game is won by checkmating the opponent's king, i.e. threatening it with inescapable capture.

There are also several ways a game can end in a draw. In the current political minefield, the political chess game is such that there are two polar sides to the political divide - the governing side and the opposition side. In the chess game, both the white and black control an army of chess species. In like manner, both sides to the political divide try to organize their armies so that they pull a mass action. The only difference is that in the political chess game played, there are no rules of the game.

Dragging the national reforms to the mud of political bickering It became clear that both sides to the political divide were using the reforms as a political pawn to showcase their political strength against each other. A critical question has been how to insulate the national reforms from political mud to which they have been thrown with the hope that there would be progress. However, the national reforms take place within a political context that dictates their direction. This viewpoint is buttressed by Professor Kapa, who puts forth two strands of arguments. One, he charges that the national reforms were borne out of a political quagmire and as such, they are inevitably a political exercise. Two, all laws that are promulgated out of the reforms should be passed through parliament, which in itself, is a house of politicians.

Therefore, it would be amateurish to suggest that there could be a way of separating the reforms from politics. On the other hand, Dr Letsie opines that the political class of Lesotho does not differentiate between national issues that of public interest and partisan interests of their political parties. Dr Letsie argues that political parties reduced the issue of national reforms to numerical strength when they got to parliament. He laments that there is a lot of dishonesty on the side of the opposition as those that are now opposing everything that the government is putting forth as a proposal on the way forward on reforms were once in government. He posits that the DNA of Lesotho’s politics is such that politicians take different political postures depending on which side they are at the time. Was a bipartisan approach not viable for resuscitation of the reforms? In mature democracies, of which Lesotho is not one yet, there are issues that are considered by all sides to the political divide as being ‘no compromise issues’ or ‘irreducible minimals’ or what some would call ‘fundamentals of the nation.’ These are the issues around which the nation, devoid of political affiliations or any other association, with all its citizens, naturally rally behind.

This can only happen when there is a natural rallying point for the Basotho nation. It would be couched around an agreed set of values that the nation as a whole cherishes. The reforms were originally given the status of a national agenda around which all Basotho to rally. This is because the reforms remain to be the final hope for Basotho after they have been failed by their political, civil society, faith base and other leaders. When they dictated the trajectory of the reforms during nationwide consultations, they pinned their hopes on the reforms as presenting a rejuvenation, a renewal and revitalization of their various shades of society. The reforms also present a rare opportunity for the nation to chart its political, economic, social or cultural when all and sundry seems to have failed.

The development partners and the diplomatic community also rallied behind the nation to drive the national reforms agenda, which would, if done properly, salvage the country from the doldrums to which it had been thrown for more than five decades. Naturally, it was expected that all shades of the nation would rally behind the reforms, without recourse to their little cocoons - political formations, civil society movements and religious affiliations. Natural expectation was also that political players, from whom a lot was expected as they are conferred with a mandate by voters to lead the national reforms agenda, would, leave out their little political cocoons and place a high premium on the reforms. However, they tended to cling to these little political cocoons to the detriment of everything and everyone. The nation expected that political parties would unanimously agree to pass any laws and constitutional amendments without subjecting them to a vote. However, this looks like a pipedream. Instead, during consultation meetings, they threatened the ruling parties with their intent to deny the nation a two-thirds majority required to pass the 10th Constitutional Amendment Bill. Their intent to place the spanners on the work of the reforms became eminent when they frustrated the reforms process.

Most Read

New coalition government-in-waiting unveiled

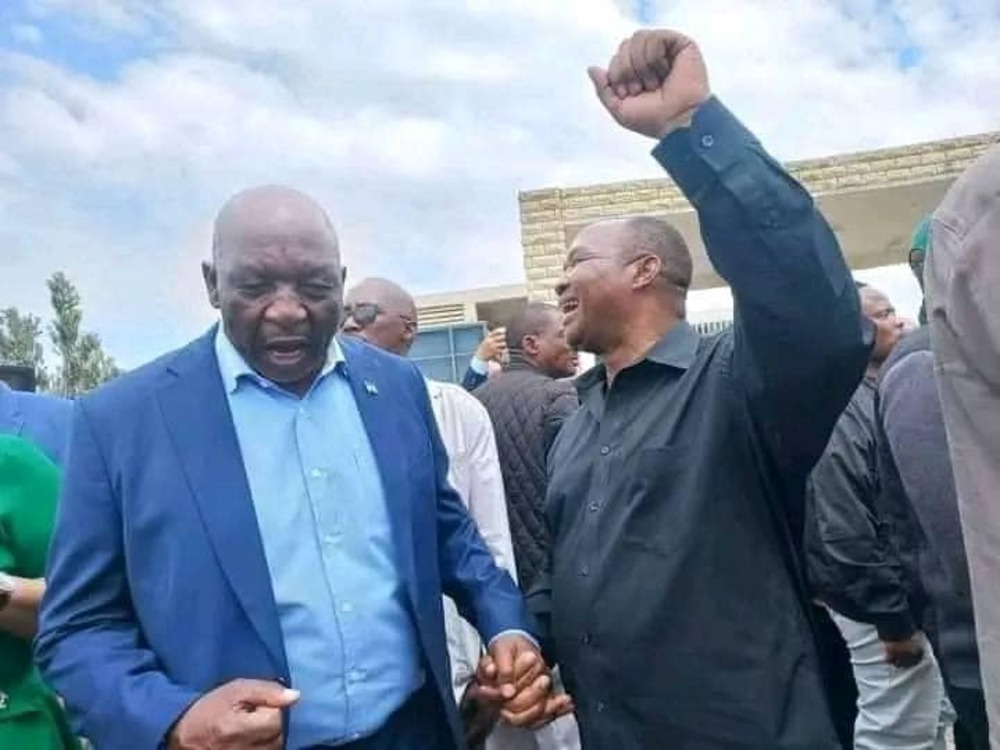

The cooling of the political temperatures came with the BAP joining the bandwagon after a season of political agitation and chess games, reflecting political anomalies in the system of political governance of Lesotho:

A Comprehensive Analysis of Lesotho's Textiles and Garment Sector

Related Stories

Politics of power-brokering, power-sharing, trading positions and changing power relations, resulting in a re-organised Government

The Lusaka Declaration 2023 at a glance:

The opportunistic character of Lesotho’s politics foils a no-confidence vote:

Opinion Vote Polls

Do you think the existing government is going in the right direction to benefit the people of the country?

Subscribe for your daily newsletters

Enter your email to subscribe to our newsletter.